People who get roughly 7 hours of sleep a night tend to have longer telomeres. People who get five hours or less have much shorter telomeres.

Think about the last time you felt sleep-deprived. Your body probably felt tired and achy, your attention was all over the place, you forgot some important information, or you felt irritable towards those around you. Maybe you spent too much money at Starbucks for an afternoon caffeine boost or ran a stop sign. What you might not have noticed is that poor sleep mucks with your regulation of emotions as well. Sleep deprivation amplifies our emotions (both positive and negative) and makes our stress responses larger—cue an awkward, aggressive rant at the coworker who definitely stole your stapler.

Getting even one night of poor sleep can throw our hormones out of whack. We may develop high levels of cortisol (the stress hormone), and insulin (the hormone that regulates our blood sugar), and ghrelin (a hormone that makes us hungry). That’s why sleep deprivation is thought to be one of the major highways to obesity.

Getting full sleep restoration on subsequent nights can normalize these changes.

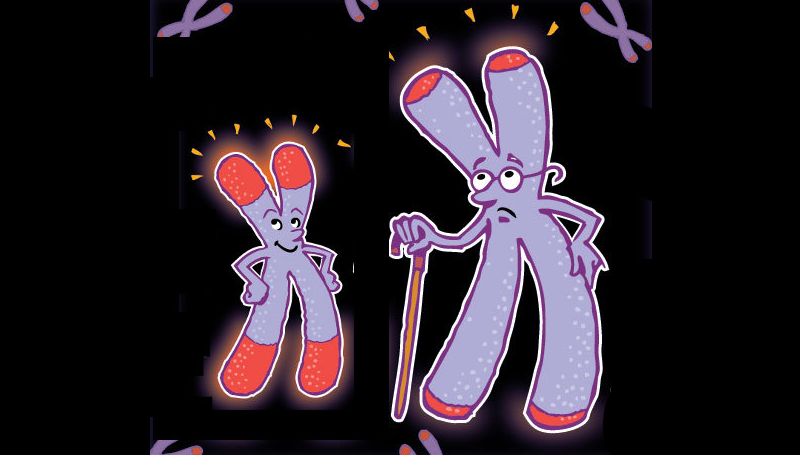

Chronic sleep deprivation affects us on a cellular level. Not surprisingly, your telomeres like being well-rested just as much as you do–people who get roughly 7 or more hours of sleep a night tend to have longer telomeres, especially among the elderly. People who get five hours or less have much shorter telomeres. Hedge your bets and get 7 or more hours of sleep as often as you can.

There are other aspects of disrupted sleep that are also associated with shorter telomeres. Sleep apnea creates oxidative stress, a chemical known to shorten telomeres. It’s thus not surprising that sleep apnea appears to be linked to shorter telomeres. Insomnia and snoring also appear to matter.

Studies have linked longer telomeres with better brainpower, a reduced risk of diseases, and a longer life. And here’s the part relevant to all of us: Getting good sleep quality is related to longer telomeres.

Elizabeth Blackbrun — along with Jack. W. Szostak and Carol W. Greider — was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for her help in discovering “how chromosomes are protected by telomeres.”