PART 1 PART 2

The CES ultra underscores its use of its conductive rubber ear clips. The rationale behind it is some interesting science on the ear; especially the vagus nerve and the special role it plays in the body. Read on.

Ref: Wandering nerve could lead to range of therapies

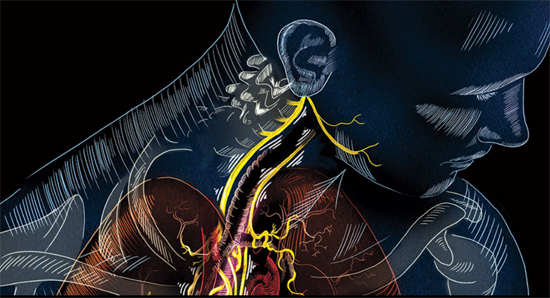

With outposts in nearly every organ and a direct line into the brain stem, the vagus nerve is the nervous system’s superhighway. About 80 percent of its nerve fibers — or four of its five “lanes” — drive information from the body to the brain. Its fifth lane runs in the opposite direction, shuttling signals from the brain throughout the body.

Doctors have long exploited the nerve’s influence on the brain to combat epilepsy and depression. Electrical stimulation of the vagus through a surgically implanted device has already been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration as a therapy for patients who don’t get relief from existing treatments.

Now, researchers are taking a closer look at the nerve to see if stimulating its fibers can improve treatments for rheumatoid arthritis,

SUPER-HIGHWAY The vagus nerve runs from the brain stem down the neck and into the abdomen, reaching a slew of organs in the process.

Nicole Rager Fuller heart failure, diabetes and even intractable hiccups. In one recent study, vagus stimulation made damaged hearts beat more regularly and pump blood more efficiently. Researchers are now testing new tools to replace implants with external zappers that stimulate the nerve through the skin.

But there’s a lot left to learn. While studies continue to explore its broad potential, much about the vagus remains a mystery. In some cases, it’s not yet clear exactly how the nerve exerts its influence. And researchers are still figuring out where and how to best apply electricity.

“The vagus has far-reaching effects,” says electrophysiologist Douglas Zipes of Indiana University in Indianapolis. “We’re only beginning to understand them.”

The Wanderer

Anchored in the brain stem, the vagus travels through the neck and into the chest, splitting into the left vagus and the right vagus. Each of these roads is composed of tens of thousands of nerve fibers that branch into the heart, lungs, stomach, pancreas and nearly every other organ in the abdomen. This broad meandering earned the nerve its name — vagus means “wandering” in Latin — and enables its diverse influence.

The nerve plays a role in a vast range of the body’s functions. It controls heart rate and blood pressure as well as digestion, inflammation and immunity. It’s even responsible for sweating and the gag reflex. “The vagus is a huge communicator between the brain and the rest of the body,” says cardiologist Brian Olshansky of the University of Iowa in Iowa City. “There really isn’t any other nerve like that.”

The FDA approved the first surgically implanted vagus nerve stimulator for epilepsy in 1997. Data from 15 years of vagus nerve stimulation in 59 patients at one hospital suggest that the implant is a safe, effective approach for combating epilepsy in some people, researchers in Spain reported in Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery in October. Twenty of the patients experienced at least 50 percent fewer seizures; two of those had a 90 percent drop in seizures. The most common side effects were hoarseness, neck pain and coughing. In other research, those effects often subsided when stimulation was stopped.

Early on, researchers studying the effects of vagus stimulation on epilepsy noticed that patients experienced a benefit unrelated to seizure reduction: Their moods improved. Subsequent studies in adults without epilepsy found similar effects. In 2005, the FDA approved vagus nerve stimulation to treat drug-resistant depression.

Although many details about how stimulation affects the brain remain unclear, studies suggest that vagus stimulation increases levels of the neurotransmitter norepinephrine, which carries messages between nerve cells in parts of the brain implicated in mood disorders. Some antidepressant drugs work by boosting levels of norepinephrine. Silencing norepinephrine-producing brain cells in rats erased the antidepressant effect of vagus nerve stimulation, scientists reported in the Journal of Psychiatric Research in September.

Against the Swell

Vagus stimulation for epilepsy and depression attempts to target the nerve fibers that shuttle information from body to brain. But its fifth lane, which carries signals from brain to body, is a major conductor of messages controlling the body’s involuntary functions, including heart rhythms and gut activity. The nerve’s southbound fibers can also be a valuable target for stimulation.

Around 15 years ago, scientists determined that the brain-to-body lane of the vagus plays a crucial role in controlling inflammation. While testing the effects of an anti-inflammatory drug in rats, neurosurgeon Kevin Tracey and his colleagues found that a tiny amount of the drug in the rats’ brains blocked the production of an inflammatory molecule in the liver and spleen. The researchers began cutting nerves one at a time to find the ones responsible for transmitting the anti-inflammatory signal from brain to body.

“When we cut the vagus nerve, which runs from the brain stem down to the spleen, the effect was gone,” says Tracey, president and CEO of the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research in Manhasset, N.Y. Later research indicated that stimulating undamaged vagus fibers also had anti-inflammatory effects in animals.

Vagus stimulation prompts release of acetylcholine, Tracey and colleagues reported in 2000. Acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter like norepinephrine, can prevent inflammation.

In 2011, rheumatologist Paul-Peter Tak, of the University of Amsterdam, and his colleagues implanted vagus nerve stimulators into four men and four women who had rheumatoid arthritis, an autoimmune inflammatory condition that causes swollen, tender joints. After 42 days of vagus stimulation — one to four minutes per day — six of the eight arthritis patients experienced at least a 20 percent improvement in their pain and swelling. Two of the six had complete remission, the researchers reported at an American College of Rheumatology conference in 2012.

“From a scientific perspective, it’s an extremely exciting result,” says Tak, who is also a senior vice president at GlaxoSmithKline pharmaceuticals based in Stevenage, England. Despite advances in treatments over the last two decades, rheumatoid arthritis patients need better options, he says. In 2014, Tak and his colleagues reported that vagus stimulation reduced inflammation and joint damage in rats with arthritis. After a week of once-daily, minute-long stimulation sessions, swelling in the rats’ ankles shrank by more than 50 percent, the scientists reported in PLOS ONE.

If these results hold up in future studies, Tak hopes to see the procedure tested in a range of other chronic inflammatory illnesses, including inflammatory bowel disorders such as Crohn’s disease. Studies in animals have shown promise in this area: In 2011, researchers reported in Autonomic Neuroscience: Basic and Clinical that vagus stimulation prevented weight loss in rats with inflamed colons.

Treating inflammatory conditions with vagus stimulation is fundamentally different from treating epilepsy or depression, Tak says. More research with patients will be necessary to develop the technique. “We are entering a completely unknown area, because it’s such a new approach,” he says. There could be financial hurdles as well, he says. But GlaxoSmithKline, which Tak joined after initiating the arthritis study, has purchased shares of SetPoint Medical, a company in Valencia, Calif., that produces implantable vagus nerve stimulators, Tak says.

As he and others put stimulation to the test for inflammation, some scientists are attempting to see if manipulating the nerve can help heal the heart.

Read more Part 2