Throughout the winter and spring of 1981, British music circles reverberated with news of Pete Townshend’s repeated transgressions. The lead guitarist and chief composer for the Who rock band was said to be drinking his breakfast and popping pills as if they were children’s gumdrops. After gaining international recognition for his pioneering rock operas Tommy and Quadrophenia, Townshend now seemed to be sinking ever deeper into drugged oblivion. At London’s trendy Soho clubs, he became the instigator of countless shouting matches and fights. Then there was the disastrous concert that March at the Rainbow, where the musician incensed the rest of the band by launching into long discordant codas and improvising on the spur of the moment. By the fall, gossip columnists had begun spreading rumors about his flirtations with heroin. There was even talk about one sordid night at the Club for Heroes, a New Romantic venue, where Townshend collapsed on the verge of death.

Pete Townshend’s close associates watched his metamorphosis from Dr. Jekyll to Mr. Hyde with both confusion and concern. Why should the voice that had belted out such fiery teenage anthems as “My Generation” and “Won’t Get Fooled Again” suddenly falter? How could the fist that had banged out electrifying guitar riffs become the perpetrator of senseless barroom brawls? Why had rock’s spiritual leader become so dispirited?

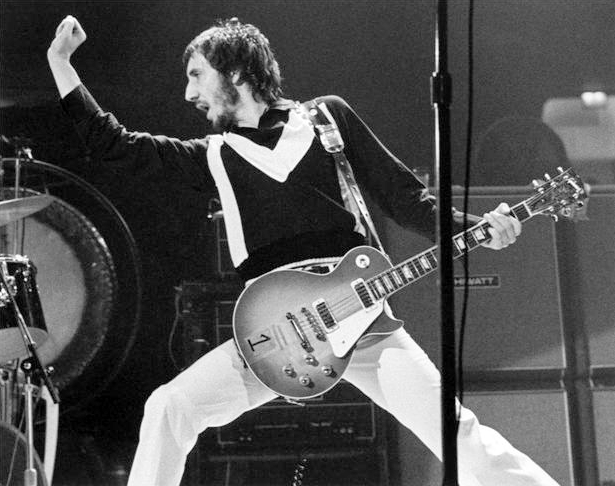

Whatever personal horrors had triggered this crisis, Townshend was unquestionably back in form by the time the Who began its final farewell tour of North America last autumn. For the 1.2 million fans who attended the forty concerts, the wayward rock star appeared to have been restored to all his former glory. Stirring the crowds to a frenzy, Townshend bunny-hopped across the stage and, without missing a beat, executed one dazzling leap after another. Flailing his guitar in the dizzying, whirligig strokes that had become his trademark, the thirty-eight-year-old musician displayed the same gusto that marked his early performances at the Marquee Club, that steamy dance hall where the Who first captured the hearts of a generation nearly two decades ago. Only this time around, there was none of the sloppiness — the bad notes or ill-timed overtures — that had so often marred their youthful deliverance. The band was tight, demonstrating a flawless virtuosity almost unprecedented in its eighteen-year career.

Back at the hotel room after the concert, Townshend confirmed that he was off drugs. He looked trim and fit. Only his jaded blue eyes, windows on a frazzled soul, hinted that some scars remained. Despite the dramatic upswing in his life, it was clear that the turbulent past continued to weigh on his conscience. Having only narrowly escaped the same fate as the Who’s late drummer Keith Moon, who died of a drug overdose in 1978, Townshend was grateful to be alive. And so he spoke at great length about his miraculous salvation.

Miraculous, in this instance, may be an understatement, for the cure Townshend underwent seems to have reversed two years of dissipation. in ten days. The secret behind his startling rebound, he divulged, is NeuroElectric Therapy (NET) — a novel method of detoxification that is currently awaiting clinical approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. This unusual treatment involves a Walkmanlike device that transmits a tiny electrical signal to the brain via electrodes taped behind either ear. Townshend wore this portable gadget — or the “black box,” as he nicknamed it — day and night during the initial phases of treatment. He claims that it rapidly cleansed his body of drugs without the painful withdrawal symptoms that usually make going “cold turkey” such an unbearable ordeal.

The black box is the brainchild of a middle-aged Scottish surgeon, Dr. Meg Patterson. Her explanation of its scientific rationale provides insight into the experience of her celebrity patient. According to Patterson, who is something of a celebrity herself among the higher echelons of rock management, the black box quickly redresses chemical imbalances in the addict’s brain. She believes the weak current stimulates the production of various neurotransmitters, notably the brain’s own opiatelike painkillers, the endorphins (for “morphine within”). Because the frequency of the electrical current appears to determine which chemical reactions will occur, Patterson has to fine-tune the signal for each type of addiction. With Townshend, who suffered from multiple addictions, she applied several different frequencies over the course of treatment.

Her remedy appears to have worked, for the disheartened musician experienced what can only be described as a rebirth. And his case is by no means unique. Townshend himself first learned of NET through blues guitarist Eric Clapton, whom Patterson weaned from heroin in 1974. Since then, she has successfully reformed over a dozen top recording stars, including such notorious drug abusers as Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones. Townshend felt compelled to speak out about Patterson’s work both to repay a personal debt and to draw attention to her enormous behind-the-scenes contribution to the music industry as a whole.

Of course, some psychological problems remained, and in the interview that follows, Townshend talks with disarming candor about the difficulty of facing up to his own failings and the even greater challenge of healing badly strained relationships with his family, friends, and members of the band — bassist John Entwistle, vocalist Roger Daltrey, and drummer Kenney Jones. But for the most part, the nightmare had ended by the time he talked with Omni magazine editor Kathleen McAuliffe in the fall of 1982.

McAuliffe told us: “Certainly in the artistic arena, there were abundant signs that his life had come together. Not only had the Who’s final tour received rave reviews in the music press, but their latest album, It’s Hard, had been hailed as their most powerful work since Who’s Next. Townshend’s two solo albums, Empty Glass and All the Best Cowboys Have Chinese Eyes, released two years later, had also won broad critical acclaim.

“These recent successes, however, seemed less important to Townshend than the need to put his past in perspective. Yet his frank disclosures, he later confided, served no cathartic purpose. He was trying to share, not shed, his immediate past, presumably so that others might learn from his experience.”